- Blog

- Research and Engineering

- Biometric performance at a billion person scale

Biometric performance at a billion person scale

In this article, we show that iris recognition technology is capable of distinguishing individuals on a billion person scale. We discuss different operating modes and evaluate the expected failure rates as the user base grows.

Intro

In order to get a rough estimation on the required performance and accuracy of Worldcoin's biometric engine, let's assume a scenario with a fixed biometric model, i.e. it is never updated such that its performance values stay constant.

Failure Cases

A biometric identification system can fail in two ways: It can either identify a person as some different person, which is called a false match or it can fail to re-identify a person although this person is already enrolled to the biometric database, which is called a false non match. The corresponding rates - the false match rate (FMR) and the false non match rate (FNMR) - are the two critical KPIs for any biometric system.

For the purposes of our analysis, we will consider three different systems with varying levels of performance.

- One of the systems, as reported by John Daugman in his paper, demonstrates a false match rate of at a false non-match rate of .

- Another system, represented by one of the leading iris recognition algorithms from NEC, has performance values as reported in the IREX IX report and IREX X leaderboard from the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST). These values include a false match rate of at a false non-match rate of .

- We also incorporate conservative estimates for current technology when deployed to an uncontrolled, outdoor environment that represented the worst case estimate when Worldcoin was conceived. These values include a false match rate of at a false non-match rate of

For a more in-depth examination of how we obtained these values from various sources, please refer to the provided link to our additional notes.

Effective Dual Eye Performance

The values mentioned above pertain to single eye performance, which is determined by evaluating a collection of genuine and imposter iris pairs. However, utilizing both eyes can significantly enhance the performance of a biometric system. There are various methods for combining information from both eyes, and to evaluate their performance, we will consider two extreme cases:

- The AND-rule, in which a user is deemed to match only if their irises match on both eyes.

- The OR-rule, in which a user is considered a match if their iris on one eye matches that of another user's iris on the same eye.

The OR-rule offers a safer approach as it requires only a single iris match to identify a registered user, thus minimizing the risk of falsely generating a second user for the same person. Formally, the OR-rule reduces the false non-match rate while increasing the false match rate. However, as the number of registered users increases over time, this strategy may make it increasingly difficult for legitimate users to enroll to the system due to the high false match rate. The effective rates are given below:

On the other hand, the AND-rule allows for a larger user base, but comes at the cost of less security, as the false match rate decreases and the false non-match rate increases. The performance rates for this approach are as follows:

False Matches

The probability for the i-th (legitimate) user to run into a false match error can be calculated by the equation

with being the false match rate. Adding up these numbers yields the expected number of false matches that have happened after the i-th user has enrolled, i.e the number of falsely rejected users. Derivation can be found here.

A high false match rate significantly impacts the usability of the system, as the probability of false matches increases with a growing number of users in the database. Over time the probability of being (falsely) rejected as a new user converges to 100%, making it nearly impossible for new users to be registered.

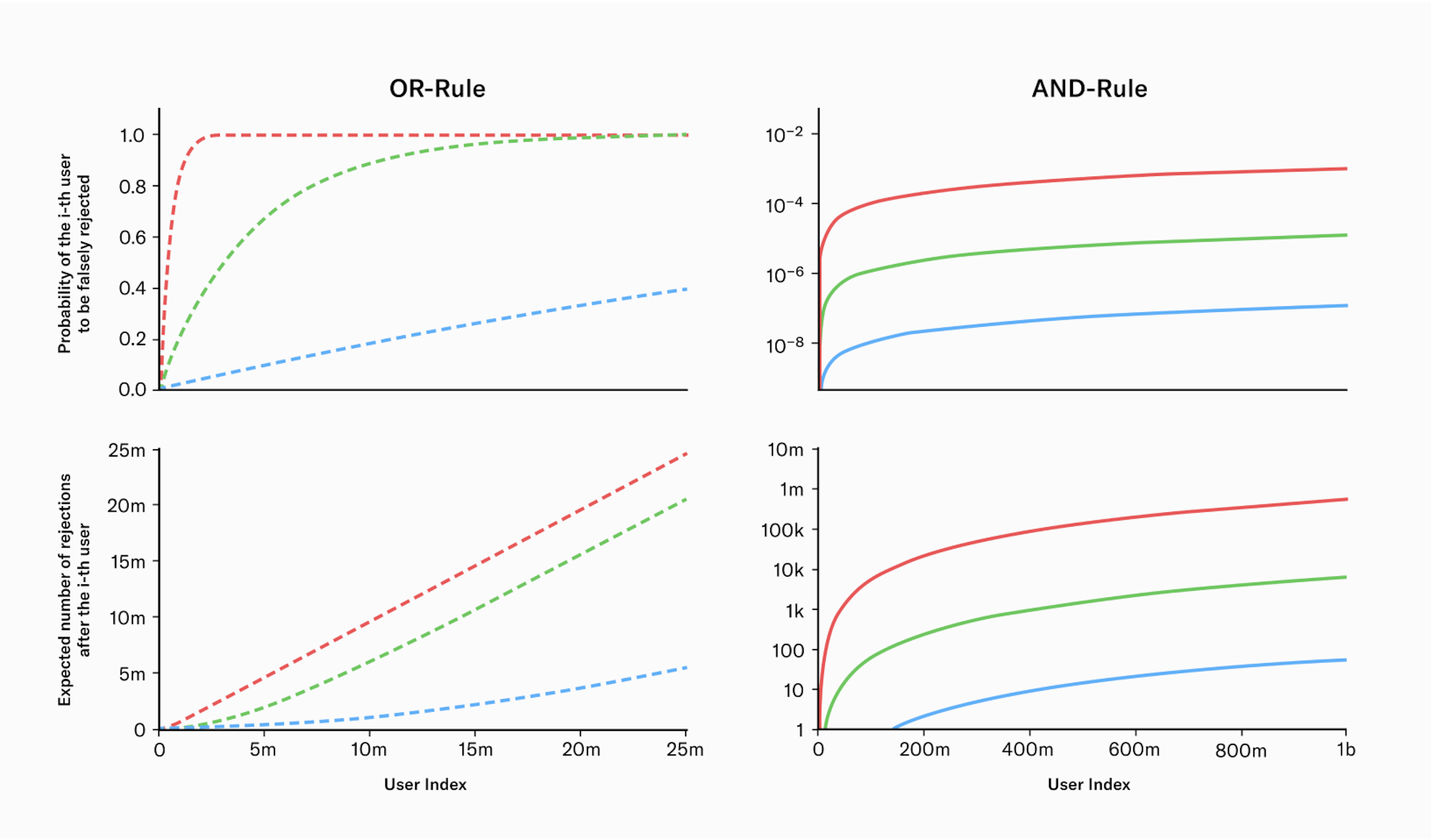

The following graph illustrates the performance of the biometric system using both the OR and AND rule. The graph is separated into two sections, with the left side representing the OR rule and the right side representing the AND rule. The top row of plots in the graph shows the probability of the i-th user being falsely rejected, and the bottom row of plots shows the expected number of users that have been falsely rejected after the i-th user has successfully enrolled. The different colors in the graph correspond to the three systems mentioned earlier: green represents Daugman’s system, blue represents NEC’s system, and red represents the initial worst case estimate.

Fig. 1

Performance of biometric systems under both the OR and AND rule across three distinct scenarios: The blue line represents a highly performant system from NEC, while the green line reflects performance values as reported by John Daugman. The red line indicates a system with conservative performance values.

The main findings from the analysis indicate that when using the OR-rule, the system's effectiveness breaks down with just a few million users, as the chance of a new user being falsely rejected becomes increasingly likely. In comparison, operating with the AND-rule provides a more sustainable solution for a growing user base.

Further, even the difference between the worst case and the best case estimate of current technology matters. The performance of Worldcoin's biometric algorithm has been continuously improving due to ongoing research efforts. This has been achieved by pushing beyond the state-of-the-art by replacing various components of the uniqueness verification process with deep learning models which also significantly improves the robustness to real world edge cases. At the point of writing this blog post, the algorithm's performance closely resembled the green graph depicted in the figure above when in an uncontrolled environment (depending on the exact choice of the FNMR). This is an accomplishment noteworthy in and of itself. Nonetheless, we anticipate further improvements in the algorithm's performance through ongoing research efforts. The optimum case is a vanishing error rate in practice on a global scale.

Note that for a large number of users () and a very performant biometric system () the equation above becomes numerically unstable. To calculate the number of rejected users for such a scenario we Taylor expand the critical part of the equation around small values of .

The derivation of the above equation can be found here. Inserting this in the equation above yields

which is a valid approximation as long as

False Non Matches

When it comes to fraudulent users, the probability of them not being matched stays constant and does not increase with the number of users in the system. This is because there is only one other iris that can cause a false non-match - the user's own iris from their previous enrollment. Thus, the probability of encountering a false non-match is given by

The number of expected false non matches can be calculated with

with j indicating the j-th untrustworthy user who tries to fool the system.

Conclusion

We conclude that iris recognition can establish uniqueness on a global scale. Further, to onboard billions of users, the algorithm needs to operate using the AND-rule. Otherwise, the rejection rate will be too high and it will be practically impossible to onboard billions of users.

The current performance is already beyond the original conservative estimate and we expect the system to eventually surpass current state-of-the-art lab environment performance, even if subject to an uncontrolled environment: On the one hand, the custom hardware comprises an imaging system that outperforms typical iris scanners by more than an order of magnitude in image resolution. On the other hand, current advances in deep learning and computer vision offer promising directions towards a “deep feature extractor” - a feature extraction algorithm that does not rely on handcrafted rules but learns from data. So far the field of iris recognition has not yet leveraged this new technology.

Links

Chris Brendel and other members of the Tools for Humanity Team